Author’s note: This article is dedicated to the victims of the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. It contains words and attitudes which, while formerly in common use, are now recognized as racist and demeaning.

The November 14, 1918 (page one) issue of “The Kelowna Record” informed its readers of the deaths of ten men – eight Chinese, one Japanese, and one Indo-Canadian – all victims of the Spanish flu. The names of these ten men were not included in the article, nor do they later appear in subsequent reporting about the Spanish flu. It is doubtful that photographs of these influenza victims exist. The names of these ten men were dutifully added to Kelowna Cemetery’s burial records, allowing historians to identify these unfortunate Spanish flu victims.

Lum Lock, Quon Ho Lock, and sons Lum Fling Lock and Hang Sing Lock, Circa 1913. One of Kelowna Chinatown’s few families.

One week later, the same newspaper raised the total of Chinese deaths to nine. It also reported on the purported Chinese beliefs about the Spanish flu’s origins:

…Chinamen (a racially-charged term, frequently used by the printed media) Kelowna have discovered the cause of the outbreak of Spanish ‘flu’ among them and the consequent deaths. It has been caused by an evil spirit, which has taken upon itself the disguise of a young white boy of about six years of age, or slightly more. The spirit appears to have been somewhat timid and has lurked around outbuildings and courts in preference to coming into the lighted stores and dwellings. Further it has only appeared after dark, but that it exists and has been visible there is not the slightest doubt – to the Chinese. The Spirit is assuming the guise of a boy of a white race, it wears no shoes or stockings, and all who have seen it have been afflicted with the new disease and are believed to have died…

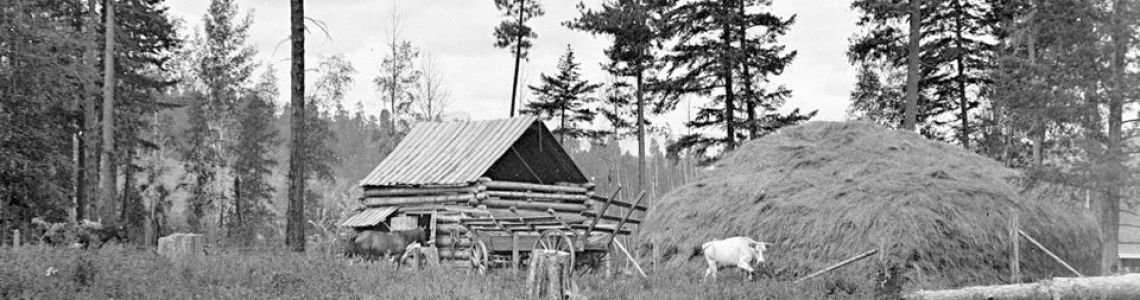

Most 1918 Central Okanagan residents were much more fortunate than the residents of Chinatown. They resided in rural areas, their nearest neighbours living at a distance, greatly lessening the chance of the disease passing between humans. Glenmore, Ellison, Rutland, South and East Kelowna, and Westbank had small populations, their citizens living on isolated farms and orchards. The people who lived within the borders of the City of Kelowna usually had some distance between themselves and their neighbours, reducing the chances of the flu moving through the general population.

Residents of Kelowna’s Chinatown assist a local farmer with spring planting

My mother’s relations – the Clement and Whelan families – typical of other Central Okanagan pioneer families, escaped the ravages of the Spanish flu. My Clement ancestors lived in Kelowna, but not at close quarters where they might be exposed to the flu. Whelan family members were even more fortunate, living in rural Ellison, isolated from much of the population which might carry and transmit the flu.

The November 21, 1918 edition of “The Kelowna Record” reported only four new flu cases during the previous week. In total, about 200 cases of the flu had been reported locally, 50 of these people still receiving medical treatment. The Spanish influenza was definitely waning, having exacted a heavy toll in Chinatown.

BC Vital Statistics records and burial records, from Oyama in the north to Peachland in the south, indicate that the local Caucasian population was much more fortunate than its Chinese counterparts during the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. An examination of these records and Kelowna’s two weekly newspapers suggest that one Central Okanagan Caucasian resident, Aileen Clements, succumbed to the flu.

According to her BC Death Registration, Aileen Clements, daughter of James H. and Mary Frances (nee Bartlett) Clements, died at Peachland on December 27, 1918, having been ill for one week. Her death was attributed to influenza with cerebral meningitis as an intermediate cause of death. According to her niece, Aileen and her family had contracted the Spanish influenza. Although ailing, fifteen year old Aileen took charge of her family’s activities and responsibilities, inevitably paying the ultimate price for her efforts.

I have researched other purported Central Okanagan influenza deaths, but ascertained that these deaths were not due to the deadly Spanish flu. I can find no trace of any local Indigenous people dying from the flu.

In late 1918, as Central Okanagan residents hunkered down in their homes. Unable to attend schools, church services, or meetings, they must have wondered what was happening elsewhere. Many of these people had British roots, and so their thoughts naturally turned to what was going on in their former homeland.

As the world continued to deal with the Spanish influenza, Kelowna’s newspapers provided vital information about what was happening in England. The December 5, 1918 edition of “The Kelowna Record” informed its readers that the previous week’s flu deaths in England (including London) and Wales totalled 5,100, the previous six weeks seeing no less than 32,000 deaths.

Another article, “Influenza Ravages London Districts”, on page two of the Thursday, December 26, 1918 edition of “The Kelowna Record” must have attracted much local interest:

Many dead in London are still without prospect of burial. The situation is most serious in the districts of Hackney, Bethnal Green, Homerton and Poplar. In many houses at Hackney bodies have been awaiting burial for ten days. Undertakers have so many orders on their hands that they can guarantee no dates for funerals. At Homerton undertakers displayed the notice: “No further orders can be taken until further notice.” The cemetery authorities are doing their best to meet the difficulty by allowing Sunday funerals. Meanwhile, the “flu” continues although less severely.

Residents in other British Columbia towns and cities suffered the effects of the 1918 pandemic. Powell River was so severely hit by the flu and subsequent lack of workers that production in local paper mills was curtailed, resulting in serious shortage of newsprint and reducing the thickness of Vancouver’s daily newspapers. Fernie, in the East Kootenay, had no less than 300 cases of Spanish influenza, with 63 deaths recorded in that community.

Kelowna’s November 28, 1918 newspaper reported that 1,550 people in Alberta had succumbed to the Spanish flu.

By mid-December of 1918, life in Kelowna was returning to normal. Schools re-opened, church services resumed, meetings were scheduled, places of amusement – including the “Dreamland” moving picture theatre – opened for business, and the community celebrated the world’s first peacetime Yuletide in five years. As the Spanish flu took leave of the community, Kelowna residents let out a collective sigh of relief and appreciation.

Much of the community escaped relatively unscathed, as the Spanish flu retreated.

Local Chinese residents, however, were not so fortunate. Losing nine members of this tightly-knit community was a devastating blow, a poignant reminder that life in “the good old days” could be challenging and cruel.

By Robert M. (Bob) Hayes

This article is part of a series, submitted by the Kelowna Branch, Okanagan Historical Society. Additional information is always welcome at P.O Box 22105 Capri P.O., Kelowna, BC, V1Y 9N9.

0 Comments