Last week’s article provided some history of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic which decimated the world’s population, claiming millions of lives, making it arguably the twentieth century’s most lethal pandemic.

As the summer of 1918 rolled into fall, the Spanish flu carved a deadly swath across the world. The second and most deadly of the flu’s three waves, it attacked Europe, Asia, Africa, Australasia, South and North America. Only Antarctica, populated by a handful of scientists and explorers, escaped the Spanish flu’s wrath.

When the first documented case of the flu was reported at Victoriaville, Quebec, on September 8, 1918 – possibly brought to Canada by Polish troops stationed in the United States – it became a matter of “when”, and not “if”, the flu would attack the Okanagan. Kelowna’s weekly newspapers regularly reported the flu’s progress, as it moved westward across Canada, making “stops” often with deadly impact on local populations.

Central Okanagan residents were therefore not surprised when the Spanish flu arrived in the valley in late October 1918. They had the opportunity to learn valuable lessons from areas earlier ravaged by the flu: the flu was easily transmitted between people; there was no known cure for the flu; isolation and quarantine helped stem the flu’s advance; and people had to act decisively do deal with the flu.

And they acted very decisively. The October 17, 1918 edition (page three) of “The Kelowna Record” announced that:

The boys’ conference in connection with the “Canadian Standard Efficiency Tests” which was to have been held in Kelowna Friday, Saturday and Sunday of this week-end, has been postponed indefinitely. The committee in charge of the affair decided upon this course in consultation with Dr. Knox [medical health officer] in consequence of the danger at the present time of introducing Spanish Influenza into the district by bringing in so many visitors from outside points. No cases of the disease have yet appeared in Kelowna and it was felt that the holding of such a conference at which boys and speakers would be present from several other towns and cities, was taking too grave a risk.

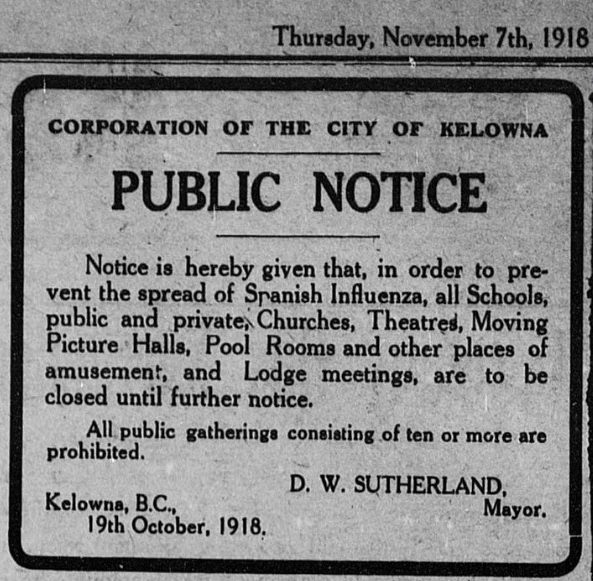

Kelowna’s elected officials were also taking precautions. On October 19, 1918 – before the flu arrived in the Okanagan – Mayor D.W. Sutherland issued a proclamation “to prevent the spread of Spanish Influenza”, by closing all public and private schools, churches, theatres, moving picture halls, lodges, and poolrooms. Gatherings of ten or more people were prohibited, to curb the spread of the deadly virus.

An emergency committee was formed “to look after all matters respecting the control of Spanish influenza.” Dr. W.J. Knox was appointed as the community’s medical health officer, fulfilling this mandate with dedication and determination.

1918 notice of cancellation of gatherings in Kelowna

The October 31, 1918 edition (page one) of “The Kelowna Record” reported about a letter to Kelowna City Council, from Len Hayman, Okanagan Lake boat captain. Hayman suggested that a tent be erected on the wharf at the foot of Bernard Avenue, where incoming lake boat passengers would be disinfected as they disembarked at Kelowna. This forward-thinking suggestion was sent to the emergency committee, for further consideration.

Kelowna was preparing for the inevitable arrival of the Spanish flu.

With preparations made in anticipation of the Spanish influenza’s arrival – including social isolation and cancellation of all school classes, church services, and social gatherings – Kelowna residents and their elected officials were confident that they had averted a potential disaster. The local newspapers reported that the Central Okanagan had been spared the ravages of the flu. They were wrong.

An article on page one of the November 7, 1918 edition of “The Kelowna Record” reported: The epidemic of “flu” in Kelowna was giving every sign of dying out without much trouble when last week-end things took an alarming turn in Chinatown. Conditions there with the over-crowding, lack of ventilation, and lack of sanitary arrangements are highly favorable to the spread of a disease like “flu” and as might have been expected, a large number of cases were noticed and four deaths occurred within a couple of days. This called for prompt action. The medical health officer, Dr. Knox, promptly ordered the quarantining of Chinatown…

Local Chinese were not allowed to leave Chinatown. An emergency hospital, serving the residents of Chinatown, was opened in Lum Lock’s building on Ellis Street. Another segregated hospital, for local Japanese residents, was opened on Harvey Avenue. These two medical facilities remained open until Christmas.

While local Indigenous and Caucasian populations were not heavily impacted by the Spanish influenza, this cannot be said of other communities. Within two weeks, nine residents of Kelowna’s Chinatown, one Japanese-Canadian, and one Indo-Canadian – young males – succumbed to the dreaded contagion:

- Thim Lee: died November 4, age 39 years

- Way Gin: died November 4, age 35 years

- Tin Wong: died November 4, age 28 years

- Wong Jui: died November 4, age 26 years

- Fong Mah: died November 4, age 36 years

- Toy Ling: died November 4, age 26 years

- Iwas Hanudo: died November 9, age unknown

- Lee Kin Do: died November 10, age 31 years

- Jung Yuen-Long: died November 11, age 28 years

- Delipa Singh: died November 13, age 29 years

- Kong Wing Gow: died November 18, age 38 years

The bodies of these eleven local men were conveyed to the Kelowna Cemetery, where the Chinese and Japanese were laid to rest in that cemetery’s non-white sections. The bodies of the nine Chinese victims were later disinterred and returned to China for re-burial. The graves of Iwas Hanudo and Delipa Singh – located in what is now Kelowna Pioneer Cemetery – are currently unmarked.

Dr. W. J. Knox, Kelowna’s Medical Health Officer, during the Spanish Influenza pandemic

It is not surprising that the deaths in Chinatown were unknown by much of Kelowna’s population for several days. Kelowna’s Chinatown was isolated from the rest of the community. Located on the south side of Leon Avenue and the north side of Harvey Avenue, between Abbott and Water streets, Chinatown was a world unto itself. Many of its residents worked in Chinatown, seldom venturing into the city.

During the growing season – April through October – many Chinese men left their homes in Chinatown, relocating to outlying Central Okanagan farms and orchards, where they worked and lived as agricultural labourers. Following the autumn harvest, they returned to Chinatown, to spend the winter with their fellow countrymen – separated from their families in China and unable to re-unite with them because of the prohibitive head tax – living close together and socializing, to lessen feelings of isolation and loneliness.

Chinatown was the perfect place for the Spanish flu to take root, spread, and claims its nine victims. White people seldom visited that part of Kelowna, and many people therefore had no idea about Chinatown’s serious health issues.

When news broke that the Spanish flu had claimed nine lives in Chinatown, the rest of the community was surprised and shocked.

To be continued next week.

By Robert M. (Bob) Hayes

This article is part of a series, submitted by the Kelowna Branch, Okanagan Historical Society. Additional information is always welcome at P.O Box 22105 Capri P.O., Kelowna, BC, V1Y 9N9.

0 Comments