Today’s article – the first of a three-part series – examines the worldwide implications of the Spanish influenza. Next week’s article focuses on how this 1918 pandemic affected Central Okanagan residents.

This article is not intended to cause fear or upset, by linking or comparing 1918 circumstances and the current global health concerns. It was written to inform readers about an event which occurred 102 years ago and is not designed, in any way, to shape our responses to the COVID-19 outbreak.

The 1992 Oxford Modern English Dictionary defines pandemic as “(of a disease) prevalent over a whole country or the world”. During the twentieth century, our planet experienced several pandemics, including the 1918 Spanish influenza, 1957 Asian influenza, and the 1968 Hong Kong influenza.

Two million people died worldwide from the Asian flu, while the Hong Kong flu claimed about 34,000 victims. Estimates of worldwide deaths from the Spanish flu vary greatly, ranging from 10 million to more than100 million people. Arguably, it was the twentieth century’s most deadly pandemic.

The Spanish influenza – also known as “la grippe” or “the Spanish Lady” – had three distinct waves: early 1918; late 1918 and early 1919; and 1919 and 1920. The second wave, brief in duration, was the most deadly, accounting for millions of deaths, most in October and November of 1918.

Spanish influenza was caused by the H1N1 virus, the organism responsible for the 2009 swine flu outbreak. This virus originated in animals – probably swine or birds – and was transmitted to its unknowing human hosts, where it quickly and efficiently mutated.

The Spanish flu did not originate in Spain; of that, we are certain. What came to be known as the Spanish influenza first made itself known in early 1918, its origins generally cited as northern China, a World War I British army base in France, or the American mid-west. As early as February of 1918, three influenza deaths in Haskell County, Kansas were dutifully reported to health officials in Washington, D.C., who promptly disregarded their significance, aiding the flu’s spread to the general population.

That this pandemic occurred during World War I (1914-1918) is not surprising. During those turbulent years, there was a large-scale movement of humanity – troops and civilians alike – retreating from the ravages of war or entering or leaving the theatres of battle. Rail transport, a fast and efficient method of transportation during those tumultuous years, was as an efficient way of unknowingly moving the virus from country to country, inevitably resulting in a pandemic.

World War I is remembered for its reliance upon trench warfare. Life in the trenches was terrible and challenging, as soldiers on both sides of the conflict spent days and months living outdoors, slogging through foul and muddy trenches, while breathing damp and fetid air.

Unburied bodies, grim reminders of bloody battles, rotted in “no man’s land” – the narrow strip of land which separated the battling armies and their trenches – ideal breeding grounds for a deadly cocktail of illness, including the Spanish influenza.

Meanwhile, far from the scenes of war, large parades and fundraising events – in aid of the war effort – brought together tens of thousands of people, further spreading the influenza to the civilian population.

As previous stated, the Spanish flu did not originate in Spain, although it heavily impacted the population of that country. The deadly 1918 contagion was so-named because the Spanish government and press freely and openly informed the world of the flu’s intensity in that nation.

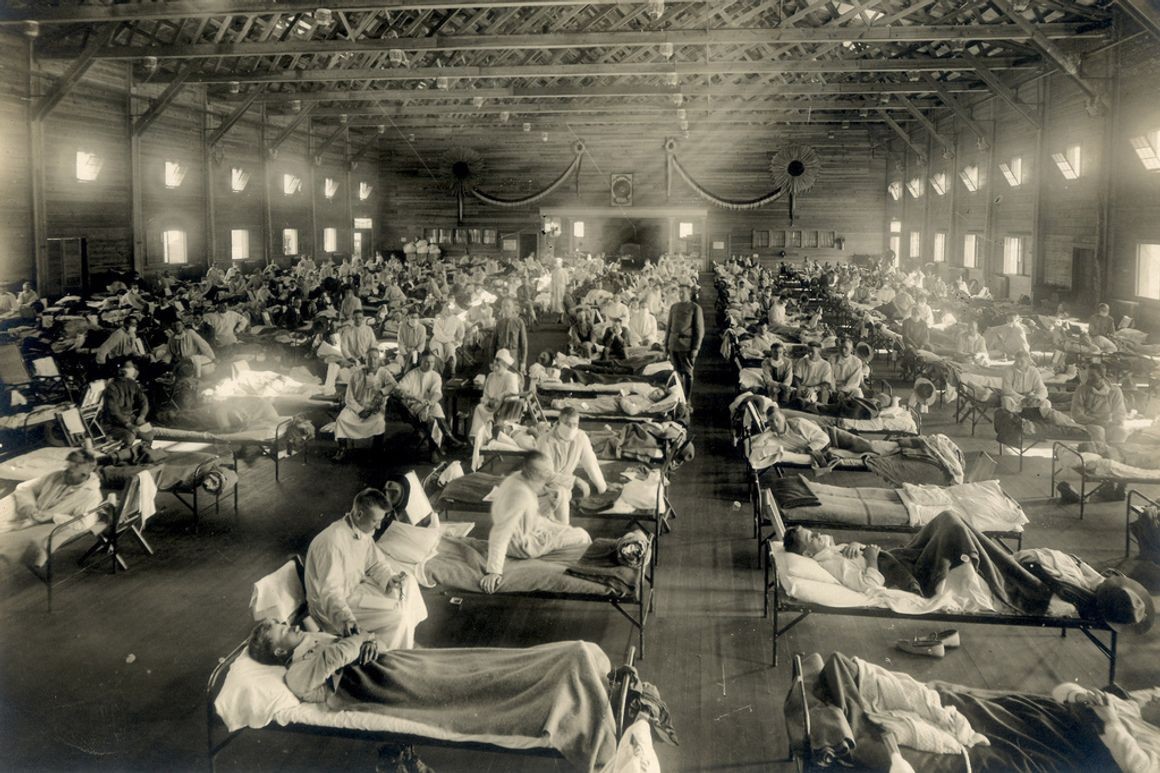

American hospital for the treatment of sufferers of the Spanish Influenza

Spain was not an active combatant in World War I and so the release of information about this rapidly-spreading ailment – including the number of deaths and the circumstances surrounding these deaths – did not negatively impact upon that country’s war effort, as it would have done to countries such as England, Germany, Canada, and the United States; these countries’ governments feared that information about the intensity of the Spanish flu would be demoralizing, with long term effects on their involvement in the war.

By October and November 1918, the Spanish flu had spread quickly, its epicentres being Europe, North America, South America (especially Brazil), South Africa, and parts of Asia (especially Russia, India, and Japan).

Although numbers are not precise, relatively few people died in China during the late 1918 phase of the Spanish influenza. If the flu originated in China prior to 1918, many Chinese seemed to be immune to the flu when it struck again in late 1918, resulting in a surprisingly small death toll in that heavily-populated country.

The 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic had significant economic and social impacts. The war effort continued relatively unabated, but on the home front people curtailed their social activities. Schools closed, shops were shuttered, and meetings (including church services) curtailed, all as attempts to prevent people from assembling in large numbers, thereby spreading the contagion. Despite herculean efforts, the flu continued to spread, impacting millions of lives and wreaking havoc on world economies.

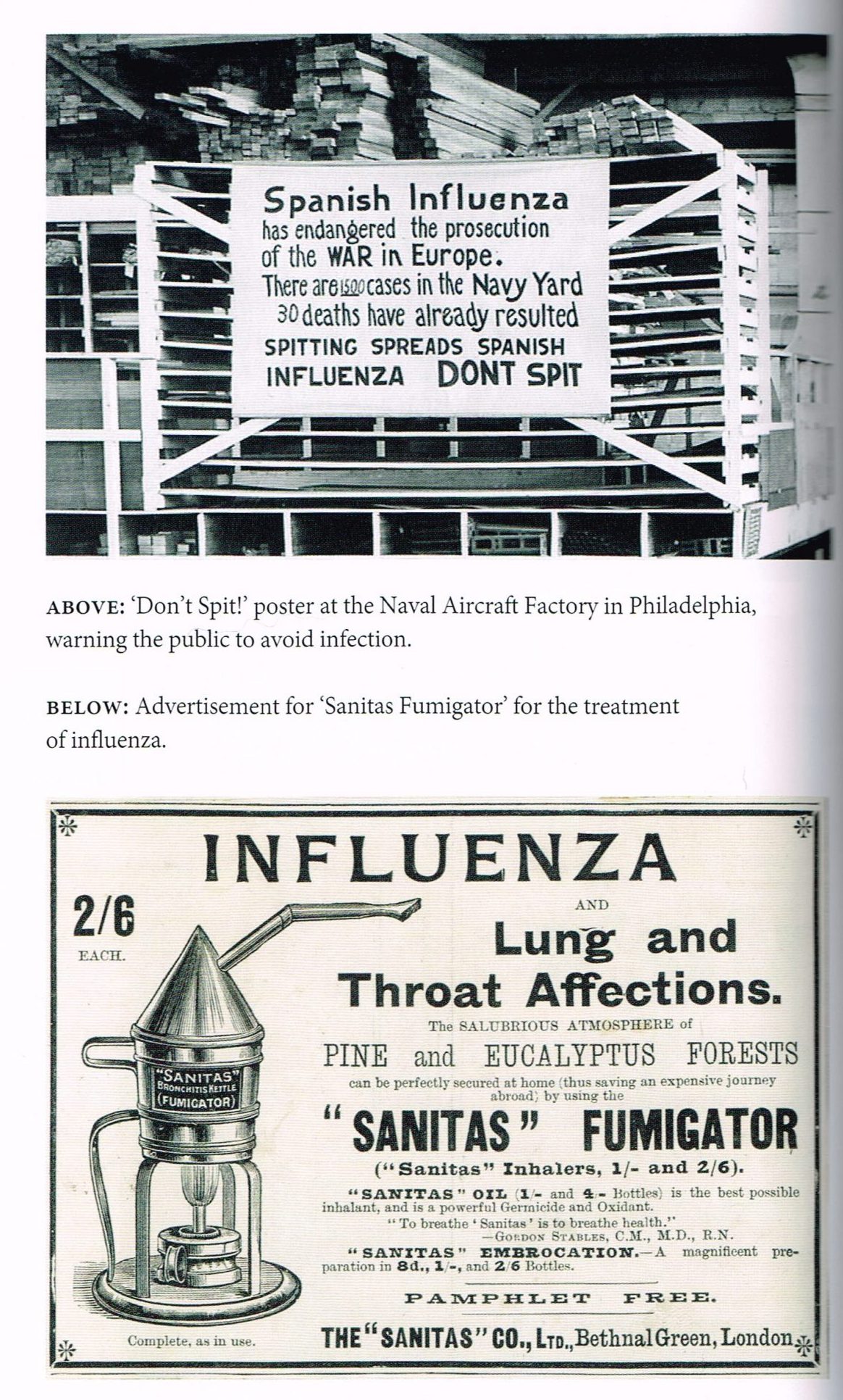

The Spanish influenza virus was largely unknown to the medical community and so treatment was challenging. Other than isolation and bed rest, little could be done for flu sufferers, opening the door to hucksters and phonies. These quacks encouraged the population to cure itself by ingesting huge quantities of items as diverse as onions and aspirin. Wearing of face masks was encouraged, with questionable results.

In the decades which followed, scientists conducted much research into the Spanish influenza, including the disinterment of victims’ bodies in northern regions, where they were preserved by permafrost. Autopsies performed on these victims show that the Spanish flu was especially virulent because it triggered a cytokine storm – an overreaction of the body’s immune system – often exacerbated by people’s overactive immune systems.

Surprisingly, the majority of the Spanish flu’s victims were young and generally healthy, atypical of epidemics and pandemics which usually target a population’s youngest and oldest citizens or individuals with pre-existing health issues or compromised immune systems.

The Spanish flu targeted the young and healthy, with deadly results.

Typically, flu victims did not long suffer once exposed to the virus. People would complain of a slight fever and cough, which quickly escalated in severity, the infected person either making a slow recovery or dying within hours or days. Death was often due to pneumonia, as the victim’s lungs were impacted by the contagion.

Advertisement in an English periodical for the “Sanitas” Fumigator, purported to be a treatment for the Spanish Influenza.

Sometimes, death was attributed to other factors, including malnutrition or meningitis. There are reported incidents of flu victims dying unexpectedly, while walking down the street or sitting in their homes, blood haemorrhaging from their lungs and noses.

Some victims “drowned” because of their immune system’s reaction to the Spanish flu virus. Desperate to throw off the virus, their bodies produced large quantities of frothy liquid, filling their lungs and causing a quick and dramatic demise, sometimes preceded by the throwing up of large quantities of thick, viscous blood.

The first documented case of the Spanish influenza in Canada was recorded at Victoriaville, Quebec on September 8, 1918. In less than two months, the dreaded contagion made its way across Canada, from coast to coast to coast, eventually claiming about 50,000 Canadians.

As 1918 dragged on, with the end of hostilities finally in sight, the world watched in horror as the Spanish flu relentlessly spanned the globe. In October and November 1918, the final six weeks of the dreaded world-wide conflict, the flu claimed millions of victims. As the horror of war subsided, the flu took its place…with deadly consequences.

People in the Central Okanagan were not oblivious to what was happening, on the war front and in the battle against the Spanish influenza. Stories of suffering and death reached the Okanagan, and local residents were not surprised or unprepared when the flu arrived on our doorstep in early November 1918, days before the signing of the November 11th Armistice. This part of the Spanish influenza’s history will be presented in next week’s article.

Postscript: “Pandemic 1918” by English historian Catharine Arnold is an excellent source of history about the Spanish influenza, including its appearance in Canada. I obtained my copy of this book from Mosaic Books in Kelowna, where copies are currently in stock or can be ordered.

By Robert M. (Bob) Hayes

This article is part of a series, submitted by the Kelowna Branch, Okanagan Historical Society. Additional information is always welcome at P.O Box 22105 Capri P.O., Kelowna, BC, V1Y 9N9.

0 Comments