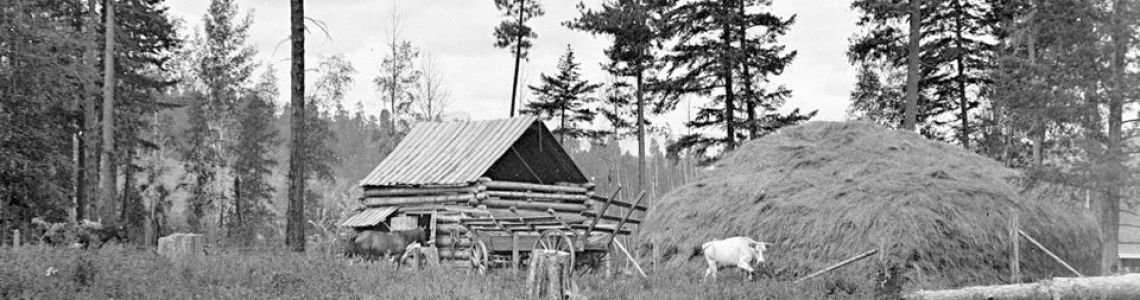

We’ve got problems right now. Big problems. But in 1893 they had some pretty wild problems! Thanks to a copy of a letter from the BC Archives, the Lake Country Museum has a unique glimpse into what life was like in Vernon in 1893.

The letter’s written by Judge Spinks of Vernon to the Attorney General’s office—serious stuff!

Here are just a few of the Judge’s complaints (the spelling is exactly as he wrote it):

- The water supply (an irrigation ditch) is “fouled by animal and vegitable matter”. (Gross)

- Some wells are only a “very few feet from cess-pools”. (What? Even in 1893, cess pools—or septic tanks—were supposed to be built 100 feet from any well, spring, or stream of water. Stands to reason that the judge also complained of “diarrhoea for water drinkers” although he does clarify that only a few of those water drinkers were residents. Wonder what the other residents were drinking…)

- Garbage thrown in the streets

- “Bed-room slops and kitchen water are just thrown outside the houses.” (Wait. Bed-room slops? What on earth was coming out of bedrooms sloppy?)

- A man named Gilmour from Victoria (clearly a city slicker) has “built a number of stores some of which are occupied as dwelling houses. The privies [outhouses] for these stores adjoin the main walls of the buildings and the cess-pools are almost under the main-buildings.” (Again, gross.)

- Plus, the Kalamalka Hotel is just letting their hogs run loose! Quite unacceptable, although our judge acknowledges the necessity of these hogs as scavengers. He seems slightly more tolerant of loose hogs than bed-room slops being tossed on the street.

The judge concludes his letter by assuring the Attorney General that he is not exaggerating. He accuses the local Council of wrongfully stating they can do nothing, and—perhaps rightfully—stating they are waiting for the Attorney General’s health act. He requests the act be “as stringent as possible”.

Indeed, the first British Columbia health act was passed in 1893. Although it has changed and grown substantially in the past 127 years, keeping our communities safe from disease remains a top priority.

It was right around 1893 that viruses were being discovered—although pioneers of virology like Pasteur, Chamberland, and Mayer were yet to identify and label them as such. The concern for many British Columbians back then was smallpox. One of the provisions in the original act was for municipalities to build facilities/hospitals specifically for people with smallpox. It was during a time when there was no public health insurance, and things like smallpox were a massive threat to communities.

Now, the Ministry of Health is responsible for building and maintaining hospitals, and all British Columbians have access to health care. We’re facing new threats, but we’re still committed to protecting our communities. Hygiene, sanitation, and hogs may no longer warrant a letter to the Attorney General, but we certainly find them essential!

About the writer: Carmen Klassen and her family have recently moved to Lake Country after living abroad for the past six years. She grew up a little south of here and is delighted to be back home. Carmen writes articles for clients around the world, and has published a series of contemporary women’s fiction novels. You can find her at www.carmenklassen.com.

Duane Thomson

Despite not knowing a lot about viruses, Judge Spinks was certainly aware of the health risks of drinking contaminated water. Interestingly, he implies that the number of water drinkers was small. This throws a new light on the propensity of the population to be heavy drinkers. Hotels and saloons would give patrons a choice of beverage. “Would you like a shot of whiskey or water from the local irrigation ditch?”It was a good thing that the temperance movement didn’t reach its stride for another couple of decades.