Lake kokanee near extinction

The Daily Courier

September 26, 1994

The sight of rotting fish floating belly up in Mission Creek is an irresistibly gruesome attraction for Jason Wilder.

Like most nine-year-olds, Jason can get pretty excited by dead things, especially if they’re in an advanced state of decay.

“Gross, there’s another one over there,” Jason said Sunday afternoon as he pointed to the disintegrating cream-colored carcass of a kokanee.

Despite Jason’s morbid interest, a dead kokanee is not unusual in September as the landlocked salmon expire soon after spawning.

But what is unusual and extremely worrying for anglers, biologists and anyone else who cares about the future of Okanagan Lake is just how few kokanee, dead or alive, there are this fall.

Kokanee have thrived for millennia in the Okanagan, but they may have come to the verge of extinction in just the past few years.

“It’s quite possible there won’t be any fish at all in the creek next year at this time,” said Peter Dill, an Okanagan University College biologist.

Rapid urban growth that has destroyed natural habitat coupled with a botched attempt to “improve” the natural food supply in Okanagan Lake are blamed for the calamitous decline of kokanee stocks.

As recently as the mid-seventies, there were more than a million kokanee spawning each year in the Okanagan, most of those in Mission Creek in Kelowna.

By 1991, the number was 9O,000. In ’92, 60,000. Last year, 30,000.

With only about two weeks left in this spawning season, only 2,000 kokanee have been counted in the creek.

“We don’t know if they’re just late or if they’re simply not coming. But it is very low for this time of year,” said Brian Jantz, regional fisheries technician for the Ministry of Environment.

“It’s a real question mark if the kokanee are going to survive. Right now, they’re on the edge,” Jantz said. “Obviously, there’s a message there that we’re doing something wrong. ”

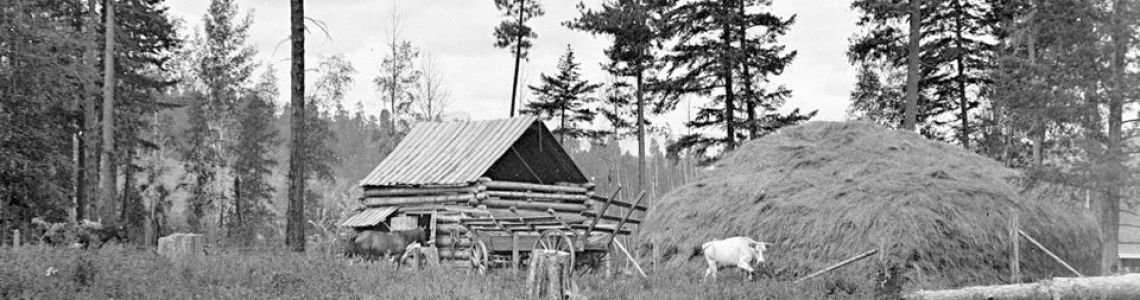

At the turn of the century, kokanee were so plentiful in the 50 or so streams that feed into Okanagan Lake that Indians used to scoop them up with nets.

Oldtimers can recall that every fall, streams would turn blood red as millions of the fish returned to spawn after spending three or four years in the lake.

“The creeks were so jammed with fish you could practically walk across them without getting your feet wet,” Howard Hazelman recalled as he joined about 1,800 other people wandering along Mission Creek during the annual Fisheries Awareness Day, put on by local sportsmens clubs and the Ministry of Environment.

“It’s hard to believe it could have changed so much,” Hazelman, 66, said as watched a handful of the kokanee struggle to haul themselves over a series of small weirs in the specially built spawning channel.

Of the natural spawning habitat that existed a century ago, biologists estimate that probably only about 10-20 per cent remains today. The rest has been lost to development, with water diverted for commercial and residential projects.

Logging, agriculture and other upstream uses have also introduced potentially harmful chemicals in many of the creeks that once supported large numbers of kokanee.

Scientists think the single most important factor in the demise of the kokanee stocks is also man-made but, ironically, it was part a project designed to help the fishery, not hurt it.

A tiny form of shrimp was supposed to provide more food for rainbow trout, but the shrimp have eaten a lot of the plankton the young kokanee also rely on.

“Now the shrimp are almost impossible get rid of,” said Dill, the OUC biologist. Fisheries officials are reluctant to make much of an effort for fear of causing some of the equally unforeseen disruption in the natural food chain.

Instead, they’ve focused on restoring and enhancing natural spawning charnels where the survival rate for eggs laid by kokanee rises 30-40 per cent from the 10 per cent common so-called ‘wild streams’.

But the man-made spawning channels are expensive; a proposed addition to the Mission Creek channel would cost at least $250,000. And given the sharp drop in kokanee numbers, even some fish-and-game enthusiasts wonder if there’s any point.

“It’s pretty hard to justify spending that kind of money if the kokanee are just about finished anyway,” said Ron Taylor, president of the Okanagan Region of the B.C. Wildlife Federation.

Virgil Willett, a lifelong Winfield resident, is also pessimistic.

“Thirty years ago, I could go out and has two fish in my boat in half an hour,” says Willett, 74. “A little while ago, I went out 15 times before I caught a single fish. . . they’re just not out there any more.”